‘Tis the season! Heat and its associated stress presents multiple obstacles to dairy farm profitability. Its effects decrease feed intake, increase energy demand and increase inflammatory responses. These effects rob energy from productive uses decreasing milk production, reproduction and immunity. What can be done to help cows through the inevitable stress of the season?

When it comes to cows, ambient temperature is one thing… humidity is another. Combined, they add up to a critical number, which has compound negative effects the higher it goes.

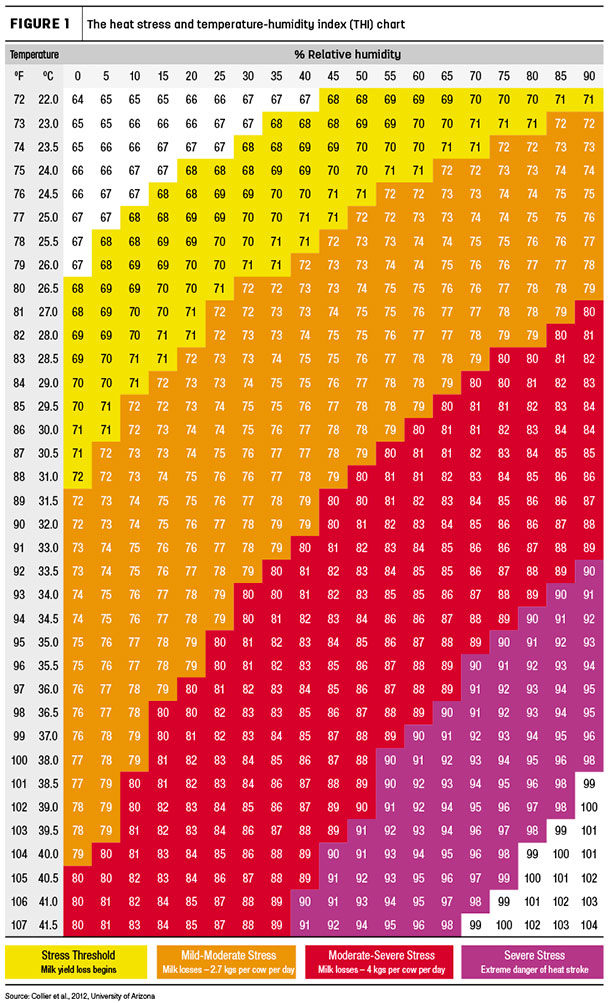

The combination of temperature and humidity yields a measurement called the Temperature-Humidity Index (THI), Figure 1. In a nutshell, cattle begin feeling the negative effects of heat stress when the THI reaches 68, and the negative effects compound as it increases from there.

Cows enter mid or moderate heat stress with a THI of 72 to 79. In this range, milk production losses of five pounds per day are likely, cow behavior changes and reproduction challenges begin to mount.

Moderate to severe heat stress kicks in with THIs greater than 80 with potential milk losses in excess of eight pounds per day and noticeable declines in animal health status and reproductive performance.

An absolute danger zone is reached as THIs exceed 90 where the difference can become a matter of life or death.

How do cows respond to increasing THIs and the associated heat stress and losses they cause? An early observation as THI creeps into the 70s is that cows spend less time lying down. When a cow lies down, the natural heat of fermentation increases her body temperature. This heat builds faster than her natural ability to shed it. This encourages cows to stand more in an effort to shed the extra heat. Of course, less lying time violates the cardinal rule that cows should lie at least 12 to 14 hours a day to rest, ruminate and increase blood flow across mammary tissues generating more energy-corrected milk.

Parallel to lower lying times, heat stress also diverts more blood flow from the GI tract outward toward the skin in an attempt to further dissipate heat. This culminates in a real challenge to hoof health while increased gut permeability leads to leaky gut, oxidative stress and systemic inflammation shunting more glucose away from milk production.

Given this risk, It’s appropriate to ask the question again; What can be done to help cows through the inevitable stress of the season?

FOCUS ON TWO PRIMARY STARTEGIES:

Strategy 1: Cow Comfort; judicious use of Shade, Wind and Water

This strategy is job one as these adaptations can deliver maximum returns on investment. Cows were built to naturally shed excess heat via radiation, conduction and convection. Again, these are effective up to the lower 70s on a THI scale. When THI rises above these levels, cows stand and begin panting, increasing respiratory rates (over 60 bpm), and modest sweating in a natural attempt to drive off excess heat.

Shade: Protect cows from excess solar radiation by using trees, building orientation and shade structures while maximizing natural air flow to the cow. Generally orient buildings, milking and feeding areas east–west to minimize sun exposure throughout the day. Placement of buildings should also avoid wind shadows such as swales or other nearby structures.

Wind: When the heat is on, dairies will need to implement ventilation systems capable of generating sufficient air movement at the cow. These systems should be installed in the milking parlor, the closeup pen and the main barn, capable to provide 250 to 500 feet per minute air speeds (3 to 6 mph) while able to scale up air exchanges to 40 - 60 times per hour (1000 to 1500 CFM per adult cow). Fans should be set to run continuously whenever ambient temperatures exceed 68º F.

Water: As THI increases above 75, it quickly becomes necessary to bolster a cow’s natural cooling ability with water, leveraging the power of evaporative cooling. This is much easier to do in dry climates than humid ones, but the principle is similar, nonetheless. Use sprinklers or soakers with droplets (not mist) large enough to wet each cow to the skin (about 1/3 gallon per cow per soaking cycle) and placed where water flow will not spoil feeds or lying areas. Wet the cows in timed cycles based on the intensity of THI spikes. For example, soaking times should run for ½ to 1½ minutes every 10 minutes when THIs are in the 70s to every five minutes when THIs get into the 80s.

The bottom line: A key metric in measuring the efficacy of your cow cooling efforts is to monitor rectal temperatures. Cows enter the heat stress zone when rectal temps exceed 102º F. Pregnancy rates and milk production metrics drop precipitously as rectal temperatures reach 102.9º F. This may be impractical to apply in all operations. Other critical KPIs to focus on include respiration rates, lying times, milk yield, feed refusal and 1st service conception rates.

Strategy 2: Nutritional – Quality Feed, Water & Key Supplemental Nutrients

Water: Cows undergo several physiological changes as they try to adapt to heat stress. Water, behind air (oxygen), can be considered the second limiting essential nutrient to life. Heat stress exacerbates the need for this essential nutrient with cows consuming 0.2 to 2.0 times more water as heat stress increases.

Keep water available in holding areas including the entry and exit from the parlor and within 50 feet of the feed bunk. There should be at least two waterers with a minimum of four inches of trough space per cow in each pen. Waterers should always be clean with adequate water flow available for peak demand.

Feed: While always important, heat stress conditions make it imperative to offer high-quality, highly-digestible forages and byproducts while synchronizing them with the appropriate sources of carbohydrates, proteins, fats and micronutrients that maintain production of energy-corrected milk, while mitigating the added health risks associated with heat stress.

Heat stress decreases both feed intake overall AND the consistency of intakes throughout the day. Simply increasing the energy density of the diet to offset the decrease in intake favors rumen bugs that increase rumen lactic acid. Increased rumen lactate paired with increased panting (respiratory alkalosis), decreased rumination and decreased bicarb rich saliva can quickly drop rumen pH. This sets cows up for an increased risk of acidosis, decreased rumen function, increased digestive upsets, gut integrity issues and increased risk of metabolic disease.

Acidotic conditions also create another issue of increasing total tract endotoxin (lipopolysaccharides or LPS) flows to the lower GI tract. Intestinal LPS increases oxidative stress and apoptosis (programmed cell death) of epithelial cells and a thinning of the mucous layer. This layer provides key barrier function enhancing absorption of nutrients while blocking toxins and pathogens from entering the body and blood stream.

Barrier function failure is commonly called ‘leaky gut’. Endotoxins (LPS), mycotoxins and pathogens penetrating this barrier incite acute inflammatory responses further activating the immune system and impairing liver function robbing glucose from productive use. The result is cattle producing less energycorrected milk with a compromised immune system. This is also an animal less likely to conceive or maintain a pregnancy.

A final point is that the calculated energy deficit of a heat stressed cow only accounts for 40 to 50% of the total milk production loss! Where is the additional drag on cow productivity beyond energy intake alone? That’s the double whammy that heat stress can cause…

As a normal course, cows in negative energy balance (NEB) exhibit reduced circulating insulin levels. At the same time, muscle and adipose tissues become insulin resistant limiting their glucose use. Cows then mobilize body fat, i.e. nonesterified fatty acids (NEFA) in an effort to balance energy needs. Circulating NEFA, when not in excess, are a significant source of energy and serve as precursors for milk fat synthesis. The thermoneutral cow in NEB uses NEFA for energy which spares glucose, which is now available for milk production.

This all changes under heat stress conditions. Heat-stressed cattle are also in NEB, except that circulating insulin levels increases which restricts the mobilization of NEFA. Heat-stressed cows with insufficient NEFA for energy become very dependent on glucose as a ‘survival’ energy source. More glucose needed for ‘survival’ results in less glucose for milk production, lowering milk yields beyond what the calculated energy deficit would suggest.

Key nutrients – supporting a cow’s ability to battle heat stress*:

McNess has a line of solutions designed to help cattle when the heat is on. We include timely and effective services that will match the best solution to your needs. Examples of solutions available include Profresh Plus, Heat Force Pak-Dairy, and CRME ™.

References available upon request

Learn more about the McNess solutions by going to mcness.com/dairy-products/#feed-and-forage